Since, then, the soul is immortal and has been born many times, since it has seen all things both in this world and in the other, there is nothing it has not learnt. No wonder, then, that it is able to recall to mind goodness and other things, for it knew them beforehand. For, as all reality is akin and the soul has learnt all things, there is nothing to prevent a man who has recalled — or, as people say, ‘learnt’ — only one thing from discovering all the rest for himself, if he will pursue the search with unwearying resolution. For on this showing all inquiry or learning is nothing but recollection.

Plato

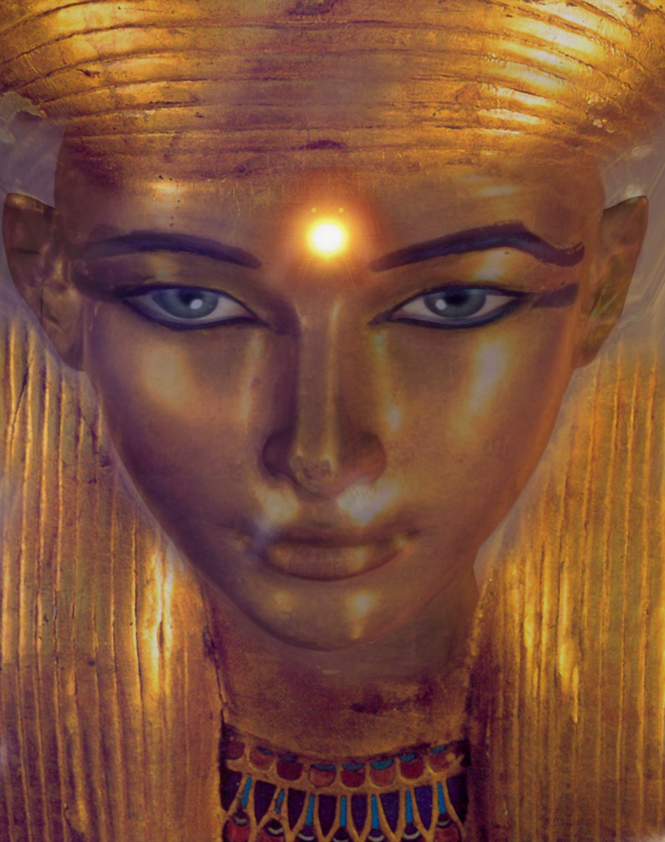

Anamnesis is true soul-memory, intermittent access to the divine wisdom within every human being as an immortal Triad. All self-conscious monads have known over countless lifetimes a vast host of subjects and objects, modes and forms, in an ever-changing universe. Assuming a complex series of roles as an essential part of the endless process of learning, the soul becomes captive recurrently to myriad forms of maya and moha, illusion and delusion. At the same time, the soul has the innate and inward capacity to cognize that it is more than any and all of these masks. As every incarnated being manifests a poor, pale caricature of himself — a small, self-limiting and inverted reflection of one’s inner and divine nature — the ancient doctrine of anamnesis is vital to comprehend human nature and its hidden possibilities. Given the fundamental truth that all human beings have lived many times, initiating diverse actions in intertwined chains of causation, it necessarily follows that everyone has the moral and material environment from birth to death which is needed for self-correction and self-education. But who is it that has this need? Not the shadowy self or false egoity which merely reacts to external stimuli. Rather, there is that eye of wisdom in every person which in deep sleep is fully awake and which has a translucent awareness of self-consciousness as pure primordial light.

We witness intimations of immortality in the pristine light in the innocent eye of every baby, as well as in the wistful eye of every person near the moment of death. It seems that the individual senses that life on earth is largely an empty masquerade, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Nevertheless, there is a quiet joy in the recognition that one is fully capable of gaining some apprehension not only of the storied past but also of the shrouded future by a flashing perception of his unmodified, immutable divine essence. If one has earned this through a lifetime of meditation, one may attain at the moment of withdrawal from the body a healing awareness of the reality behind the dense proscenium of the earth’s drama.

Soul-memory is essentially different from what is ordinarily called memory. Most of the time the mind is clouded by a chaotic association of images and ideas that impinge upon it from outside. Very few human beings, however, are in a position to make full use of the capacity for creative thinking. They simply cannot fathom what it is like to be a thinking being, to be able to deliberate calmly and to think intently on their own. Automatic cerebration is often mistaken for primary thinking. To understand this distinction, one must look at the fundamental relation between oneself as a knower and the universe as a field of knowledge. Many souls gain fleeting glimpses of the process of self-enquiry when they are stilled by the panoramic vistas of Nature, silenced by the rhythmic ocean, or alone amidst towering mountains. Through the sudden impact of intense pain and profound suffering they may be thrown back upon themselves and be compelled to ask, “What is the meaning of all of this?” “Who am I?” “Why was I born?” “When will I die?” “Can I do that which will now lend a simple credence to my life, a minimal dignity to my death?”

Pythagoras and Plato taught the Eastern doctrine of the spontaneous unfolding from within of the wisdom of the soul. Soul-wisdom transcends all formal properties and definable qualities, as suggested in the epistemology, ethics and science of action of the Bhagavad Gita. It is difficult for a person readily to generate and release an effortless balancing of the three dynamic qualities of Nature — sattva, rajas and tamas — or to see the entire cosmos as a radiant garment of the divine Self. He needs to ponder calmly upon the subtle properties of the gunas, their permutations and combinations. Sattvic knowledge helps the mind to meditate upon the primordial ocean of pure light, the bountiful sea of milk in the old Hindu myths. The entire universe is immersed in a single sweeping cosmic process. Even though we seem to see a moving panorama of configurations, colours and forms, sequentiality is illusory. Behind all passing forms there are innumerable constellations of minute, invisible and ultimately indivisible particles, whirling and revolving in harmonic modes of eternal circular motion. A person can learn to release anamnesis to make conscious and creative use of modes of motion governing the life-atoms that compose the variegated universe of his immortal and mortal vestures.

The timeless doctrine of spiritual self-knowledge in the fourth chapter of the Bhagavad Gita suggests that human beings are not in the false position of having to choose between perfect omniscience and total nescience. Human beings participate in an immense hinterland of differentiation of the absolute light reflected within modes of motion of matter. To grow up is to grasp that one cannot merely oscillate between extremes. Human thought too often involves the violence of false negation — leaping from one kind of situation to the exact opposite rather than seeing life as a fertile field for indefinite growth. This philosophical perspective requires us to think fundamentally in terms of the necessary relation between the knower and the known. Differences in the modalities of the knowable are no more and no less important than divergences in the perceptions and standpoints of knowers. The universe may be seen for what it is — a constellation of self-conscious beings and also a vast array of elemental centres of energy — devas and devatas all of which participate in a ceaseless cosmic dance that makes possible the sacrificial process of life for each and every single human being. If one learns that there are degrees within degrees of reflected light, then one sees the compelling need to gain the faculty of divine discrimination (viveka). That is the secret heart of the teaching of the Bhagavad Gita.

The Gita is a jewelled essay in Buddhi Yoga. Yoga derives from the root yog, ‘to unite’, and centres upon the conscious union of the individual self and the universal Self. The trinity of Nature is the lock of magic, and the trinity of Man is the sole key, and hence the grace of the Guru. This divine union may be understood at early stages in different ways. It could be approached by a true concern for anasakti, selfless action and joyous service, the precise performance of duties and a sacrificial involvement in the work of the world. It may also be attempted through the highest form of bhakti or devotion, in concentrating and purifying one’s whole being so as to radiate an unconditional, constant and consistent truth, a pure, intense and selfless feeling of love. And it must also summon forth true knowledge through altruistic meditation. Jnana and dhyana do not refer to the feeble reflections of the finite and fickle mind upon the finite and shadowy objects of an ever-evolving world, but rather point to that enigmatic process of inward knowing wherein the knower and the known become one, fused in transcendent moments of compassionate revelation. The pungent but purifying commentary by Dnyaneshvari states in myriad simple metaphors the profoundest teaching of the Gita. In offering numerous examples from daily life, Dnyaneshvari wants to dissolve the idea that anything or any being can be known through a priori categories that cut up the universe into watertight compartments and thereby limit and confine consciousness. The process of true learning merges disparate elements separated only because of the looking-glass view of the inverted self which mediates between the world and ourselves in a muddled manner. The clearest perception of sattva involves pure ideation.

Raghavan Iyer

The Gupta Vidya II