Author Archives: Hālau ʻĀha Hūi Lanakila

Library Suggestions

Birth Chart Calculator | TheKingdomWithin

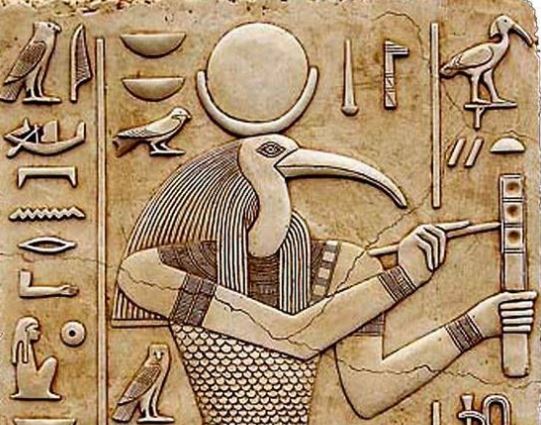

EGYPT – KINGDOM OF THE TWO HEADS | | TheKingdomWithin

If it is true that on their way out of Egypt, the “sons of Israel” took with them great treasures(1), the secrets of Egypt might then not only have been buried in the sand but also in the books written by the very people that built Egypt(2). Maybe could the study of the original scriptures of the Tanakh(3) (תנ”ך), or ancient testament, help Egyptology to answer the questions it brings up constantly and, who knows, maybe through the very Scriptures that once transformed slaves into a people of free men(4), could the community of Egyptologists reach wider horizons … But the Tanakh is made out of a powerful language hard to master. Rich in allegories, in arithmetic and poetic subtleties, it is a very high and hermetic language only a very few people can penetrate. Missing, added, doubled or modified letters, words within different words, hidden arithmetic values and anagrams(5) are among the many subtleties that lock it. This is how the number of words

Source: EGYPT – KINGDOM OF THE TWO HEADS | | TheKingdomWithin

A QUESTION ABOUT ASTRAL TRAVEL AND LUCID DREAMING | | TheKingdomWithin

A QUESTION ABOUT ASTRAL TRAVEL AND LUCID DREAMING ~ Raz Iyahu

Question: “I am now aware within the dreams, able to control them more.. ask questions, head left or right at will not mindlessly wandering through them as an observer.. (lucid dream descriptions) … we have deja vu when we keep making the same mistakes? then die and go on to a holding area until our links die off too to be brought back again? idk.. what to think… (more dream descriptions) … I know there are messages in there.. trying to figure them out… What do you think? am I maybe making this happen with my fears, or am I really being prepared for what is to come.. so confusing! Answer: “Through this lucid dreaming there are many signs and experiences that are showing us things but this is the experience of the higher awareness, the higher perception because the consciousness is still not totally connected due to a lack of will (strength). Because there is a disconnection between the lower mind and the upper

Source: A QUESTION ABOUT ASTRAL TRAVEL AND LUCID DREAMING | | TheKingdomWithin

THE SANDS OF TIME ARE SHIFTING | | TheKingdomWithin

We are at a very important time in our planetary and personal ascension process this week. We are surrounded by the symbol of infinity, the hourglass of time. We have an hourglass planetary alignment occurring today and this week. The hourglass is really the infinity symbol, which is a representation of time. Today 5/22/15 is a 8 day in numerology, which is also infinity. In addition, we have something that fully supports the “flip” of our reality that I have written about. I have addressed the fact, in earlier papers, that we live in an upside down reality. It’s a mirror image of what we are moving to. I can clairvoyantly see this and feel it, and today thanks to my friend Oka Fala, I have real proof that I am not an out of balance crazy mystic. LOL…. I love astrology, it confirms my information and makes me not feel strange! In his blog, which I will post a link for at the end of my paper…he states….this hourglass alignment occurs at the IX XI gates, these are the 9

The Occult Daily

Source: The Occult Daily

DNA shows hunter-gatherers were replaced by a mystery group after the Ice Age | Daily Mail Online

A team of scientists, led by researchers at the University of Tübingen in Germany, suggests that Europe underwent a huge population turnover 14,500 years ago as the climate warmed.

A team of scientists, led by researchers at the University of Tübingen in Germany, suggests that Europe underwent a huge population turnover 14,500 years ago as the climate warmed.

Source: DNA shows hunter-gatherers were replaced by a mystery group after the Ice Age | Daily Mail Online

Discussion – On Detachment from Overthinking

[Theosophy – Audiobook] Vegetarian Diet and Occult Practice, Vegetarianism and Occultism, Vegan, Audiobook, Magic – by C.W. Leadbeater

[Occult Lecture] The Vision of Hermes Trismegistus (Thoth), Alchemy, Hermeticism, Kybalion, Esoteric Initiation, Esotericism, by Manly P. Hall.

Discussion – Investigating the New Age Interest in the Kaballah

Exploring the Kaballah and its relation to the Tree of Life …

Birthday Meditation

Quan Yin is the Quintessential Bodhisattva … and her messages are especially poignant on your special natal day. Enjoy!

Meditation Focus …

Breathing in I am renewed with Life, breathing out I am renewed with Life. Breathing centres me in awareness.

Daily Chabad

The size of the deed is not what matters. It is only a catalyst. One small deed could be enough to ignite a process to change the entire world. One small opening is all that’s needed, and the rest will heal itself.

Whatever you do, do it with the conviction that this is the one last fine adjustment, the tipping point for the entire world.

Theosophy – The Self-Actualizing Man – II, by Raghavan Iyer

THE SELF-ACTUALIZING MAN – II

From a philosophical standpoint, we live in an age impoverished by the inability of men to find the conditions in which autonomous and fundamental thinking can take place. From a psychological standpoint, our social situation facilitates rather than hinders the widespread fragmentation of consciousness. In our daily lives, the flux of fleeting sensations is so overpowering that we are often forced to cope with it by reducing the intensity of our involvement with sensory data. All our senses become relatively dulled. The fact that we do seem to manage at some level may simply confirm the extraordinarily adaptive nature of the human organism. The key to our survival at a more self-conscious level may be the development of a new cunning and resilience in our capacity for selection. Although we do not notice most things while driving on the freeway, we do seem to display a timely awareness of that which threatens us. Our consciousness, though fragmented, may be sharpened in ways that are necessary for sheer survival. The really serious consequence of this is in regard to interpersonal encounters and relationships.

As early as the seventeenth century, John Locke observed that in a modern atomistic society, where large numbers of men are held together chiefly by impersonal bonds of allegiance to central authority, other men do not exist for any one man except when they threaten him or when they appear to him as persons who could be of advantage to him. In present-day society, we can see all too clearly how very difficult it is for even the most conscientious to retain a full awareness of their fellow citizens as individual agents, as persons who suffer pain and are caught up in unique sets of complexities. How much more difficult to see others even if strangers as persons with capacities and inner moral struggles that go beyond visible manifestations, as individuals who are more than the sum of all their external reactions and roles. We enter into most of our relationships on the basis of role specialization; and we are thereby driven, more than we wish, in our most primary affective encounters, by calculations of advantage or by fears of invasion and attack. A psychoanalyst from Beverly Hills has suggested recently that a marital relationship is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain because of the cumulative pressure of collective tension. Even though a loving couple may live together on the basis of shared memories and commitments and of close intimacy, their relationship may be unable to carry the burden of a host of social frustrations and milling anxieties that come from outside but that they cannot help turning against each other.

Given the sad predicament of the individual in contemporary society, it is hardly surprising to find various earnest-minded men vying with each other to diagnose our prevailing sickness, thereby adding to the collective gloom. Many of these diagnoses are identified with psychological and psychoanalytic approaches that are colored by a preoccupation with the pathological. In the context of this majoritarian pessimism, which goes back to Freud himself, it required a large measure of cool courage for a small band of humanistic psychologists to initiate an alternative mode of viewing the human situation. They have not evaded any of the stark facts of our present malaise, and at the same time they have dared to provide a democratized, plebianized version of a model that is humanistic and optimistic. In place of earlier concepts of the well-adjusted man, we now have the model of a man who, although (and rightly) not adjusted to existing conditions, is capable of exemplifying, releasing, living out, and acting out what is truly important to him as an individual.

Even though humanistic psychology has been launched in this country with the fanfare of a revolutionary movement, it has actually filled a vacuum created by the fatigue of monotony attendant on much of the so-called scientific psychology. Whatever else may be said about the behavioristic, reductionist, and mechanistic models of man, they are undeniably and invariably dull and unexciting. The boredom is pervasive. If one is so unfortunate as to surrender wholly to these current versions of secular fundamentalism, life loses its savour and lustre. As one critic has suggested, the worst thing about these depressing models of human behavior is not that they claim to be true but that they might become true.

It is highly significant that a crucial point of departure for the humanistic approach came from a man, Viktor Frankl, who was not merely reacting against current orthodoxy on intellectualist grounds. The necessity of a new way of looking at the human condition came to Frankl out of the depths of authentic suffering – out of the intense pain and mental anguish he experienced in a Nazi concentration camp. Indeed, many of the existentialist and phenomenological modes of thought fashionable in our society originated in postwar Europe. Frankl’s is the uncommon case of a therapist who can write with compelling conviction about man’s search for meaning. Faced with the most meaningless and unbearable forms of suffering, Frankl saw the profound significance for some prisoners of a deliberate defiance in their minds of the absurdity of their condition and the dignity of an individual restoration of meaning as a means of psychological survival. Frankl was, therefore, able to see after the war why many of his patients were unwilling to be treated as malfunctioning machines or as anxiety-driven bundles of inhibitions and neuroses. It was much more important for them to engage in the supremely private and uniquely individual act of assigning meaning to their own condition.

Frankl then took the unorthodox step of reinforcing his discovery by making a pointed reference to the classical tradition. The emphasis on the noetic (from nous) in man is fundamental to what has come to be called logotherapy. The classical concept of noetic insight could be explained in a variety of ways. A simple and very relevant rendering of the Platonic concept of insight is that it enables one man to learn from one experience what another man will not learn from a lifetime of similar experiences. In their capacity to extract meaning and significance out of a pattern or a medley of recurrent experiences, human beings are markedly different from each other. Such differences between men are acutely apparent at a time when “experience for its own sake” has become the slogan of an entire generation. The refusal to evaluate experiences by reference to any and all criteria is the sign of a deep-seated form of decadence. The rejection by the young of the imposed and restrictive criteria offered to them by their parents and professors is understandable, but unfortunately it leads many to surrender to the mind-annihilating dictum of “experience for its own sake.”

In the classical tradition, the notion of noetic insight was exemplified in an aristocratic form. The wise and truly free man was one who had so fully mastered the meaning-experience equation that he had wholly overcome the fear of death and thereby gained a conscious awareness of his immortality. His comprehension of the whole of nature, of society, and of his own self in terms of their essential meanings placed him in a lofty position of freedom from the categories of time, space, and causality. As employed by contemporary humanistic psychologists like Frankl, the notion of insight is democratized into a basic need for survival – into a desperate and ubiquitous concern on the part of struggling human beings to grapple somehow with their chaotic and painful experiences so as to extract a minimal amount of meaning.

In the writings of Abraham Maslow we are provided a portrait of the self-actualizing man in a manner that is accessible to all and yet reminiscent of the classical models of perfection. He investigated the attitudes of a fair sample of people who displayed common characteristics in relation to the way they regarded the world and themselves, despite their differences in regard to age, sex, social status, profession, and other external conditions. From his empirical observations, he tried to derive the identifying marks of a self-actualizing man. He hazards the tentative conclusion that only about one per cent of any sample out of the population of contemporary Americans are examples of self-actualizing men. This is not to suggest that in our contemporary culture only one per cent is capable of becoming self-actualizing men. Presumably, the proportion of such men would increase with a greater awareness of what is involved in becoming a self-actualizing man. As a matter of fact, the figure of one per cent is ten times higher than Thoreau’s figure of the one in a thousand who is a real man.

Maslow makes a simple but crucial distinction between deficiency needs and being needs. Human beings function a great deal of the time out of a sense of inadequacy. They seek to supply what they think they lack from the external world. This sense of incompleteness will be intensified by the experience of frustration in repeated attempts to repair the initial feeling of deficiency. But there is also in all men a sense of having something within them which seeks to express itself, which is fulfilled when it finds appropriate articulation. One of the important features of this distinction between deficiency needs and being needs is that the same need could function at different times as an expression of a sense of deficiency or of a sense of being. It is in his manner of coping with both his sense of deficiency and his sense of being that a self-actualizing man reveals his enormous capacity for self-dependence. Maslow tries to give an exhaustive list of characteristics of the self-actualizing man. We shall mention only a few, those that seem particularly significant in the context of our consideration of the subject.

An essential mark of the self-actualizing man is his capacity for acceptance. He accepts himself and the world. Although he may reject certain elements of the world around him, he has sufficient reasons for accepting the world with its unacceptable elements. The world he accepts includes the world of society and extends into the world of nature. It includes an acceptance of particular persons. This wide-ranging acceptance of the world is possible for a self-actualizing man because he has accepted himself. His knowledge of himself may be incomplete, and there may be elements in himself which he dislikes or wishes to discard. And yet there is meaning to a fundamental act of acceptance of oneself with all one’s limitations. If the act of acceptance is real, it will be strong enough to withstand all the threats from the external world. The self-actualizing man is aware of particular and partial rejections from external sources, but he can never give up on himself or on others. His essential acceptance enables him to see reality more clearly. He sees human nature as it is, not as he would prefer it to be. He will not shut out portions of the world that are unpleasant to him or that are not consonant with his own preferences and predilections. He is willing to see those aspects of reality that remain hidden to other men to the extent to which they conflict with their own prejudices. His fundamental act of acceptance also involves negation. He negates the distortion implicit in our immediate sensory responses to the world and in the exaggerated inferences derived from such immediate responses.

A second characteristic of the self-actualizing man is his spontaneity. Having made his fundamental act of acceptance, he is simple and direct and spontaneous in his responses. He is not burdened by the anxiety of calculation or by the fatigue of tortuous rationalization. He can make an appropriate yet spontaneous response in many a context, not all the time but often enough to see beyond conventionalities. In everyday human encounters, many opportunities are forfeited because of the habit of mutual suspicion. The self-actualizing man is able to negate conventional signs and symbols because he is not obsessed with social acceptance. He is not trapped by the totemistic worship of token gestures that restrict meaningful involvement. He is thereby less vulnerable to collective modes of manipulation. Consequently, he loses his sense of striving. He continues to grow through his mistakes and failures, but he grows without anxiety and without an oppressive awareness of the opinions of others or the crude criteria of success and failure. A real sense of freedom is released by his fundamental act of acceptance and by the spontaneity of his responses to the world.

A third characteristic of the self-actualizing man is his transcendence of self-concern. He centers his attention on non-personal issues that cannot be grasped at the level of egotistic encounters. He is aware of the needs that must be met in the lives of others, in interpersonal relations and in society. He does not view the problems of human beings in terms of the mere interaction of egotistic wills. He is not exempt from the tendency to ego assertion, but he refuses to participate in the collective reinforcement of ego sickness. This form of sickness arises when the ever-lengthening shadow of the ego provides a substitute world of wish fulfillment, leaving a man with no sense of the breadth or depth of reality or of having a grip on the suprapersonal core of human problems. By seeing beyond personal egos, the self-actualizing man gives himself opportunities to extend his mental horizon and re-create his picture of the world. He can move freely between larger and more limited perspectives, thereby attaining a clearer perception in relation to any problem of what is essential and what is not.

With an enlarged perspective there emerges a capacity for cool detachment and an enjoyment of privacy. A man cannot attain to true freedom if he is incapable of enjoying his own company. Many people today have become cringingly dependent on the need to interact with others, to the point of psychic exhaustion. Men are so involved in their projections of themselves in familiar surroundings that they are unable to stand back and view their activities free of egocentricism. The self-actualizing man appreciates the need for self-examination. He knows that in order to meet this need he must provide space within his time for solitude, privacy, and quiet reflection. He thus enhances his sense of self-respect and maintains it even when he finds himself in undignified surroundings or in demeaning conditions. He places his valuation of being human in a fundamental ground of being that goes beyond the levels at which he interacts with others.

Hermes, January 1976

Raghavan Iyer

Australian Cave paintings may be the oldest on the planet | Ancient Code

Theosophy – THE SELF-ACTUALIZING MAN – I, with Raghavan Iyer

THE SELF-ACTUALIZING MAN – I

The contemporary image of the self-actualizing man arose in the context of the broader concern among humanistic psychologists with a bold new departure from the pathological emphasis of a great deal of psychoanalytic literature since Freud. It is only when we see this model from a philosophical, and not merely from a psychological, standpoint that its affinities with classical antecedents become clearer. The distinction between the philosophical and psychological standpoints is important and must be grasped at the very outset.

The philosophical standpoint is concerned explicitly with the clarification of ideas and the removal of muddles. It seeks to restore a more direct and lucid awareness of elements in reality or in our statements about reality or in what initially seems to be a mixed bundle of confused opinions about the world. It is by sorting out the inessential and irrelevant that we are able to notice what is all too often overlooked. The philosopher is willing to upset familiar notions that constitute the stock-in-trade of our observations and opinions about the world. By upsetting these notions he hopes to gain more insight into the object of investigation, independent of the inertia that enters into our use of language and our ways of thinking about the world. By giving himself the shock of shattering the mind’s immediate and conventional and uncritical reactions, the philosopher seeks to become clearer about what can be said and what cannot even be formulated.

Most of our statements are intelligible and meaningful to the extent to which we presuppose certain distinctions that are basic to all thinking, to all knowledge, and to all our language. Although these distinctions are basic because they involve the logical status of different kinds of utterance, their implications are a matter for disagreement among philosophers. By discriminating finer points and nuances that are obscured by the conceptual boxes with which we view a vast world of particulars, the philosopher alters our notion of what is necessary to the structure of language, if not of reality. However, as Cornford pointed out in “The Unwritten Philosophy,” all philosophers are inescapably influenced by deep-rooted presuppositions of their own, of which they are unaware or which they are unwilling to make explicit. The philosopher makes novel discriminations for the sake of dissolving conventional distinctions. And yet, what he does not formulate – what he ultimately assumes but cannot demonstrate within his own framework – is more crucial than is generally recognised. Whether it be at the starting point of his thinking or at the terminus, the unformulated basis is that by which he lives in a state of philosophical wonderment or puzzlement about the world.

Our statement of the philosophical standpoint refers to knowledge as the object of thought but also to the mind as the knower, the being that experiences the act of cognition, the mode of awareness that accompanies the process of thinking. It is the mind that gets into grooves, that has uncriticised reactions to the world in the form of a bundle of borrowed ideas and compulsive responses. At the same time, it is the mind in which clarification and resolution are to be sought; and in the very attempt to seek clarification through new discriminations, it comes to a point where it empties itself or cannot proceed any farther. It might also experience some sort of joyous release out of the very recognition of the fullness of an enterprise that necessarily leads to a limiting frontier.

Philosophical activity, at its best, might be characterized as a patient inching of one’s way. It requires a repeated redrawing of a mental map, moving very slowly, step by step. It is most effectively pursued through a continuing dialogue among a few who respect themselves and each other enough to be able to say, “You”re a fool,” occasionally and to have it said of oneself. Such men must become impersonal by refusing to hold on to any limiting view of the self and by refraining from playing the games of personalities caught in the emotional experiences of victories and defeats. It is only by becoming impersonal in the best sense that a man is ready to enjoy a collective exploration in which there are many points of view representing relative truths, in which all formulations are inconclusive, and in which the activity itself is continually absorbing and worthwhile.

Whereas the philosophical standpoint is concerned with knowledge and perception, with clarity and comprehension, the psychological standpoint requires us to talk in terms of freedom and fulfillment, of release and of integration. Psychologically speaking, a man’s feeling that he is freer than he was before is very important to him. This condition involves a sense of being more fulfilled than he expected to be in the present in relation to his memories of the past and also in relation to his anticipations about the future. Since the experience of feeling freer is meaningful to a man in a context that is bound up with his self-image, the psychological standpoint must always preserve an element of self-reference. A man’s false reactions or wrong ideas are important to him psychologically in a way that they would not be philosophically. Regardless of whether they are true or false, good or bad, a man’s reactions to the world are a part of himself in a very real sense. If he were to surrender them lightly, he would be engaged in some sort of pretense; he might be conniving at some kind of distortion or truncation of his personality.

It may sound odd to plead in this way for the psychological importance of our self-image, because we tend to think we are crippled by a self-image that is generated by an awareness of our defects and limitations. Still, we know from our intimate relationships that to think of a person close to us in an idealized manner that excludes all his weaknesses and failings is an evasion of authenticity and may even be a form of self-love. No mental projection on a love object can be as enriching as a vibrant if disturbing encounter with a living human being. To be human is to be involved in a complex and painful but necessary awareness of limitations and defects, of muddles, of borrowed and distorting preconceptions, of antithetical and ambiguous reactions, and of much else. If we are to recognise and live with such an awareness, we cannot afford to surrender our sense of self – even if intellectually we could notice the falsity in many elements in our perceptions of ourselves and of others.

The distinction between the philosophical and the psychological standpoints may be put in this way. Whereas a philosopher is committed to an exacting and elusive conception of truth, the psychologist is concerned with the maximum measure of honesty in the existing context. Of course, one cannot maintain honesty without some standard of truth, some stable reference point from which we derive criteria applicable at any given time. On the other hand, one cannot be really sincere and determined in the pursuit of philosophical truth without being honest in one’s adherence to chosen methods and agreed procedures of analysis. Clearly, philosophy and psychology are interconnected. In the earliest Eastern and Pythagorean traditions, the pursuit of wisdom and self-knowledge were merely two aspects of a single quest. Since the seventeenth century, the impact of experimental science and the obsession with objectivity and certainty have sharpened the separation between impersonal knowledge about the external world and the subjective experiences of self-awareness; and the latter have been excluded in the psychologist’s concern with the constants and common variables in human behavior. Nonetheless, the psychologist has not been able to ignore the individual’s need for security and his feeling of self-esteem. And certainly, in the psychoanalytic concern with honesty, the element of feeling is extremely important, independent of any cognitive criteria. To feel authenticity, to feel honesty, to feel fulfillment, each is integral to the psychological standpoint. To dispense with such personal feelings and to see with the utmost intellectual objectivity are crucial to the philosophical enterprise, although the very term “philosopher” as originally coined by Pythagoras, contained, and even to this day retains, an impersonal element of eros.

We must now proceed to characterize our contemporary condition both from the philosophical and the psychological standpoints. We can see immediately that, in terms of the elevating concept of the philosophical enterprise presented so far, modern man is singularly ill-suited for it. Most men do not have the time, the energy, the level of capacity, or even the will to think for themselves, let alone to think through a problem to its fundamentals. Even professional philosophers are not immune to our common afflictions – the appalling lack of time for leisurely reflection, the pace and pressures of living, the overpowering rush of sensory stimuli. In our own affluent society, the struggle for existence is so intense that (as in Looking-Glass Land) it takes all the running we can do to keep in the same place. One’s nerves, our raw sense of selfhood, are constantly exposed to the tensions and frustrations of other people, and one’s state of being is continually threatened by this exposure because one finds one’s identity at stake. In these circumstances, it is not surprising to find that most thinking is adaptive and instrumental. The activity of the mind is largely preoccupied with the promotion of material ends or the consolidation of social status, or the gaining of some token, external, symbolic sense of achievement that is readily communicable among men. A great deal of our thinking, even the most professionally impressive, is a kind of get-by thinking.

What is the chief consequence of so much shallow thinking? For those few who are willing to question everything, take nothing for granted, and who want to think through an idea to its logical limits, it is truly difficult to function in an environment in which the emphasis is on what seems safe because it is widely acceptable. The pressure to think acceptable thoughts is double barrelled, for our thoughts may be deemed acceptable in terms of standards that are already allowed as exclusively acceptable. Acceptability is the decisive hallmark of much of the thinking of our society. Most of the time we are so anxious about how we appear to others when we think aloud our responses to any problem that we cannot even imagine what it is like to experience the intensity of dianoia, of thinking things through in the classical mode. To take nothing for granted, to think a problem through with no holds barred, regardless of how we come out or of our “image,” requires a courage that is today conspicuous by its absence.

One might say, philosophically, that thinking things through, as demanded by the Platonic-Socratic dialectic, is bound up with that form of fearlessness which is decisively tested by one’s attitude to death. We are all haunted by a feeling of pervasive futility, an acute sense of mortality, an awful fear that looms larger and paralyzes us though with no recognizable object – a fear of being nothing, a fear of annihilation, a fear of loss of identity, a perpetual proneness to breakdown and disintegration. Thus, it is enormously difficult for us to give credibility in our minds to, let alone to recognise at a distance, authenticity in any possible approximation to a state of fearlessness which dissolves our sense of time and makes a mockery of mortality. And yet this remote possibility was itself grounded by classical philosophers in the capacity of the mind to think through an idea or problem in any direction and at the same time to value the activity of thinking so much that in relation to it death and all that pertains to our sense of finality and incompleteness becomes irrelevant.

Our contemporary culture is marked not merely by a shrinking of the individual sense of having some control over one’s life and one’s environment but also by an increasing loss of allegiance to the collectivist notions of control transmitted by the political and social philosophies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Psychologically, we could characterize our age as the historical culmination of man’s progressive inability to take refuge from his own sense of vulnerability in some compensatory form of collectivist identity. If a person in our society really feels that he cannot take hold of his life, that he has no sense of direction, that he has not enough time for looking back and looking ahead, and that all around him is rather meaningless, then it is small comfort for him to be told that as an American or as a member of the human race he can exult in the collective conquest over natural resources. The repeated ideological efforts to reinforce such a sense of vicarious satisfaction are more and more self-defeating.

Hermes, January 1976

Raghavan Iyer

Daily Chabad

No one is free today because of yesterday.

Freedom is the force that renews this universe out of the void every day and every moment. It is a source of endless energy with infinite possibilities.

You are free when you take part in that endlessness. When you never stand still. When you are forever escaping the confines of today to create a wide open tomorrow.

Gnosis: The Secret of Solomon’s Temple

A Must Read for Advenced Spiritual Seekers | Ego – Alertness – Consciousness

In your present, individual state of consciousness we identify with the thoughts and emotions that appear in our mind, so we believe that we are a separate, illusionary person, an Ego. A lot of us …

Source: A Must Read for Advenced Spiritual Seekers | Ego – Alertness – Consciousness