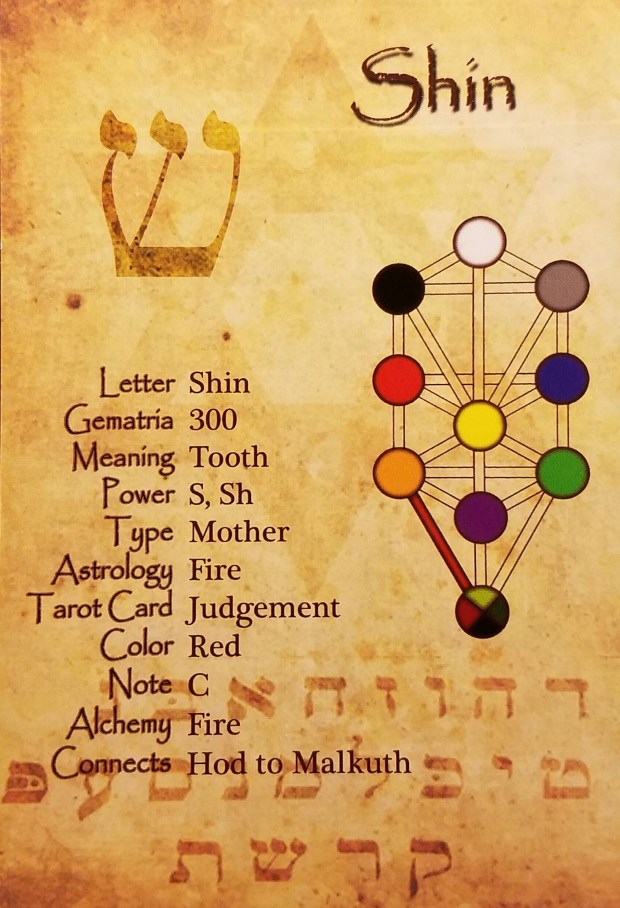

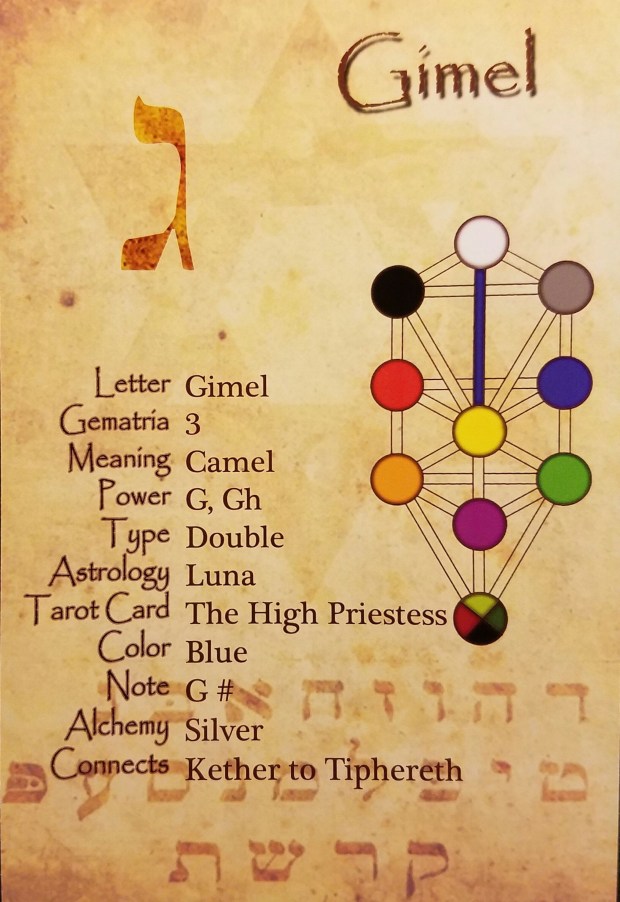

3

gimmel

rg

Ger

(The Stranger)

When a stranger dwells among you in your land, do not taunt him. The stranger who dwells with you shall be like a native among you, and you shall love him like yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

Leviticus 19:33–34

The Old Testament repeats the theme of “love thy neighbor” many times, reminding us of our own times as “strangers in a strange land” so that we’ll be more sensitive to others in repressed or minority status. Because of your own history of enslavement, whether literal or figurative, you should know how it feels to be out of your element, and make an effort to include and accept those peoples who are different from you but who dwell in your midst.

Although the time the Jews spent in Egypt was one of oppression, slavery, and humiliation, there was also a sense of having settled there, for better or worse. In fact, when Moses led the Jews out of Egypt and began the journey toward the Promised Land and liberation, half of the former slaves chose to stay behind, because to them, a familiar reality, even a horrible one, seemed better than the unknown. Even those who left with Moses at one point panicked in the face of the difficult journey and wondered if maybe they would have been better off back in Egypt, where at least they knew their routines.

In a way, this desire to return to slavery makes sense—after so many years of living in one harsh reality, it’s an enormous task to change one’s mind-set to that of a free people. This is why we must be kind to the stranger, to encourage him to adapt to his new environment rather than returning to a damaging past. And even if the stranger is just “passing through” and not necessarily joining our specific community, we should encourage him to get the most out of his journey while he’s on it.

The word Ger is usually translated as “convert,” and the verb form, Lagor, means “to dwell.” In this passage, we see that a Ger is not only someone who has officially converted into a new society or religion, but also a stranger, a foreigner who lives among a new set of people and customs. We’ve all been Gers at one point or another: We’ve moved to a new city, left home to go off to college, been transferred for work, traveled in faraway countries, or simply changed the way we look at the world, so we’ve all become converts of sorts along the way.

To some extent, this “strangeness,” the definition of a “stranger in a strange land” is essential to Kabala. It may seem odd that this phrase is used in a positive way in traditional texts. But when you look at it from a kabalistic angle, it makes perfect sense: Sometimes you need to lose yourself in order to find yourself, sometimes you need chaos in order to show you the path to order and enlightenment, and sometimes you need to take the road less traveled in order to find the right path for you.

===

The Gimmel comes to you when you’re suffering from improper judgment. You’re either feeling judged or are judging others unfairly, whether you realize it or not. You may feel like an outsider at work, in social gatherings, or spiritually. Conversely, you may feel too much like an insider, so much so that you don’t accept anyone outside of your immediate circle.

The challenge is one of identity: We all have to strike a fine balance between knowing who we are and where we’ve come from, and accepting the Other in our lives as equally valid. This is certainly not an easy task. Knowing oneself is hard enough; accepting the Other is sometimes nearly impossible.

Open yourself to new and different experiences: Hear the stories of the people you encounter on your life’s journey and appreciate where they’ve been, and share your own stories of exile and redemption. Only by opening to others and accepting them will you enlarge your worldview and be totally at peace with your own life.