The true teaching of Brahma Vach is enshrined in the secret code language of Nature. A new mode of initiation has already begun. Invisible beings in their mayavi rupas cherish the teaching, but no visible beings are entirely excluded. The quintessential teaching is conveyed in so many different ways that prepare for the sacred instructions in deep sleep, even for those struggling souls who seize their last chance in this life. The more any person can maintain during waking hours the self-conscious awareness of what is known deep within — even though one cannot formulate it — the more one can hold it and see it as blasphemous to speak thoughtlessly about it. Though such persons participate in all the fickle changes of the butterfly mind, the more attentively they can preserve and retain the seminal energy of thought with a conscious continuity, the more easily will every anxiety about themselves fade into a cool state of contentment. Like a shadow following the lost and stumbling seeker of the light, a true disciple will unexpectedly encounter the forgotten wisdom, the spiritual knowledge, springing up suddenly, spontaneously, within the very depths of his being. Then he may receive the crystalline waters of life-giving wisdom through the central conduit of light-energy, symbolized in the physical body by the spinal cord. One may walk in the world with deep gratitude for the sacred privilege of being a self-conscious Manasaputra within the divine temple of the universe for the sake of shedding light upon all that lives and breathes. In seeing, one can send out beneficent rays. In hearing, one can listen beyond the cacophony of the world. Whilst one is listening constantly to the music of the spheres echoing within one’s head and heart, one is able to send forth thoughts and feelings that are benevolent and unconditional, extended towards all other human minds. These thoughts could become living talismans for the men and women of tomorrow in the fields of cognition wherein the war between light and darkness, the living and the dead, is now being waged.

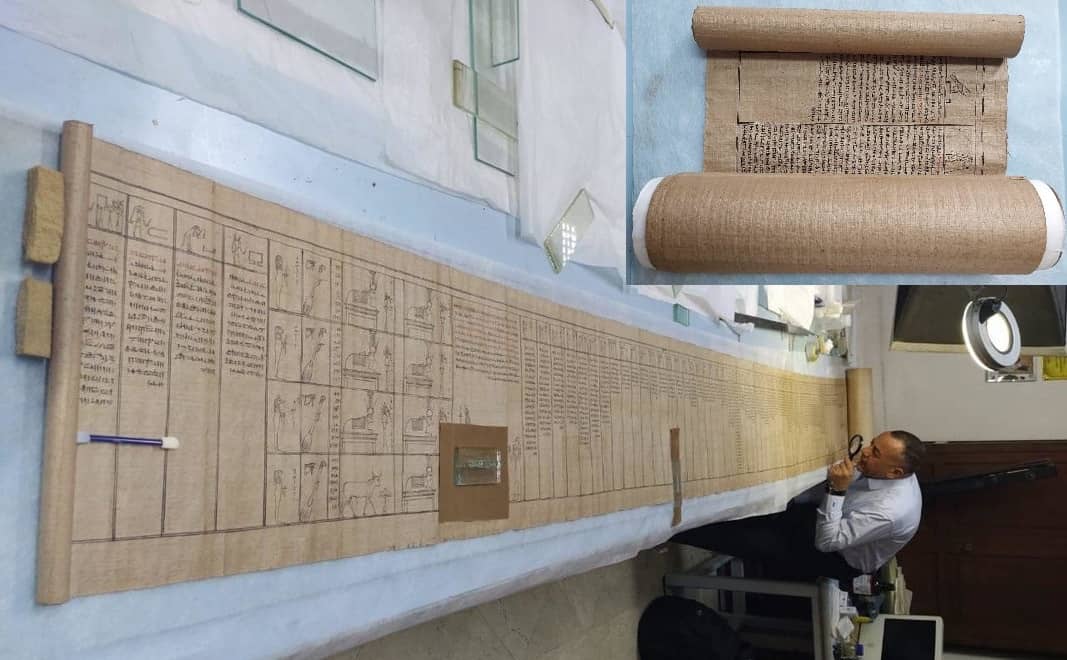

The Philosophy of Perfection of Krishna, the Religion of Responsibility of the Buddha and the Science of Spirituality of Shankara, constitute the Pythagorean teaching of the Aquarian Age of Universal Enlightenment. There are general and interstitial relationships between the idea of perfectibility, the idea of gaining control over the mind, and the exalted conception of knowledge set forth in the eighteenth chapter of the Gita. To begin to apprehend these connections, one must first heed the mantramic injunction from The Voice of the Silence: “Strive with thy thoughts unclean before they overpower thee.” Astonishingly, there was a moment in the sixties when millions became obsessed with instant enlightenment; fortunately, this is not true at present. Few people now seriously believe that they are going to die as perfected beings in this lifetime. This does not mean that the secret doctrines of the 1975 cycle are irrelevant to the ordinary man who, without false expectations, merely wants to finish his life with a modicum of fulfilment. All such seekers can benefit immensely from calmly meditating upon the Sthitaprajna, the Self-Governed Sage, the Buddhas of Perfection. This is the crux of Krishna’s medicinal method in the Gita. He presents Arjuna with the highest ideal, simultaneously shows his difficulties and offers intensive therapy and compassionate counsel. This therapeutic mode continues until the ninth chapter, where Krishna says, “Unto thee who findeth no fault I will now make known this most mysterious knowledge, coupled with a realization of it, which having known thou shalt be delivered from evil.” In the eighteenth chapter he conveys the great incommunicable secret — so-called because even when communicated it resides within the code language of Buddhic consciousness. The authors of all the great spiritual teachings like the Gita, The Voice of the Silence and The Crest Jewel of Wisdom knew that there is a deep mythic sense in which the golden verses can furnish only as much as a person’s state of consciousness is ready to receive.

H.P. Blavatsky dedicated The Voice of the Silence to the few, to those who seek to become lanoos, true neophytes on the Path. Like Krishna, she gave a shining portrait of the man of meditation, the Teacher of Mankind. In chosen fragments from the Book of the Golden Precepts, the merciful warning is sounded at the very beginning: “These instructions are for those ignorant of the dangers of the lower IDDHI.” In this age the consequences of misuse of psychic powers over many lives by millions of individuals have produced a holocaust — the harvest of terrible effects. Rigid justice rules the universe. Many human beings have gaping astral wounds and fear that there is only a tenuous connecting thread between their personal consciousness and the light of the higher nature. Human beings have long misused Kriyashakti, the power of visualization, and Itchashakti, the power of desire. Above all, they have misused the antipodal powers of knowledge, Jnanashakti, so that there is an awful abyss between men of so-called knowledge and men of so-called power. What is common to both is that their pretensions have already gone for naught, and therefore many have begun to some extent to sense the sacred orbit of the Brotherhood of Bodhisattvas. On the global plane we also witness today the tragic phenomenon of which The Voice of the Silence speaks. Many human beings did not strive with their unclean hobgoblin images of a cold war. The more they feared the hobgoblin, the more they became frozen in their conception of hope. Human beings can collectively engender a gigantic, oppressive elemental, like the idea of a personal God, or the Leviathan of the State, which is kept in motion by reinforcement through fear, becoming a kind of reality and producing a paralysis of the will on the global plane.

Today, for the first time in recent decades, we live at that fortunate moment when psychopathology and sociopathology have alike become boring, throwing the individual back upon his intuitions, dreams and secret intimations. Individuals cannot suddenly create refined vestures for the highest spiritual thought-energy, but they can at least desist from self-degradation. No protection a human being can devise is more potent or powerful than the arc of light around every human form. Any individual with unwavering faith in the divine is firmly linked with the ray descending into the hollow of the heart. One can totally reduce the shadowy self to a zero. The cipher may become a circle of sweetness and a sphere of light. It is imperative to keep faith with oneself in silence and secrecy, as every telling weakens the force that is generated. Krishna says, “In whatever way men approach me, in that way do I assist them.” This is offered unconditionally to all. Near the end of his instruction he says, “Act as seemeth best unto thee.”

Basic honesty will go far to clean out the cobwebs of delusion and confusion so that the seeds of spiritual regeneration may be salvaged. Patience is needed together with enduring trust in the healing and nurturing processes of Nature that protect the seeds silently germinating in the soil. They cannot be pulled up and scrutinized again and again, but must be allowed to sprout in the soft light of the dawn, enriched by the radiant magnetism of universal love which maintains the whole cosmos in motion. Even a little soul-memory shows that there is no need to blame history or Nature, much less the universe, for the universe is on the side of every sincere impulse. Even the most wicked and depraved man may have some hope. Even a little daily practice delivereth a man from great risk. Even a minute grain of soul-wisdom, when patiently assimilated with a proper mental posture in relation to the sacred teachings and the sacrificial Teachers, will act as a beneficent influence and an unfailing guide to the true servant of the Masters of the Verbum. This incommunicable secret of Krishna is the sweetest and most potent gift of the divine Logos of the cosmos to the awakened humanity of today and the global civilization of tomorrow.

Raghavan Iyer

The Gupta Vidya II